Internal corruption can be a tricky beast to identify and investigate, as opposed to internal fraud which – although complex to investigate – usually comes with a paper trail of some kind.

An unbalanced ledger, an unpaid supplier, or a payment without delivery, there’s usually something to go on. However, internal corruption often occurs in secret deals between people who won’t report or co-operate unless their relationship breaks down.

For example, an employee involved in a kickback scheme may inflate the price of some service by a percentage over market value, and receive a payment or some other gratuity from a vendor.

If there’s no missed payment, an apparently legitimate supplier, and the service was delivered – there’s no clear way to identify this except that the profit or balance sheet may continually suffer in that area. Internal corruption can prove to be expensive for businesses, with lawsuits impacting the business and its future.

There is one simple method to identify it that we would all be at least somewhat familiar with – at least if we’ve watched our share of gritty crime dramas – which we can use to identify and, in some jurisdictions, provide evidence for internal corruption.

How to identify internal corruption

I’m sure many of us have seen one of the above crime dramas, and noticed that they often involve a corrupt detective of some kind. Suspicion is usually raised, in ourselves or in the other characters, with a question like “How do they afford that on a detective’s salary?”. The answer in these shows is, of course, corruption.

In real life of course, it’s not that simple. We don’t know what other legitimate sources of income someone may have. However, it is a worthy question to ask, particularly in high risk industries like banking, or high risk positions like a procurement manager.

You can ask this question to raise a suspicion and start an investigation – and if you can find out your employee’s other sources of income, you can start to compare this to their expenses and determine if there is any unexplained income.

The Basel Institute on Governance, a not-for-profit institute aimed at researching and fighting corruption, calls this ‘Source and Application’ analysis. It involves subtracting a subject’s income and funds (including a starting bank balance) from known lawful sources in a specific period, from the total expenditure or accumulated funds in that period.

If there is any left over, this represents unexplained income that may be fraudulent.

The subject may be able to explain the source of the income – it may not be corruption. But if some or all of the income remains unexplained, this can be presented as circumstantial evidence in a corruption case.

In some jurisdictions, you can directly claim against this unexplained income in recoveries. At a minimum, it is a useful tool to highlight unexplained income and structure investigations to target that income.

Collating bank statements, pay slips, dividend statements and so on can help you balance out expenses on loans, rent, holidays, and so on – leaving you with only unexplained income, and clearly checked off explanations that you no longer need to look into.

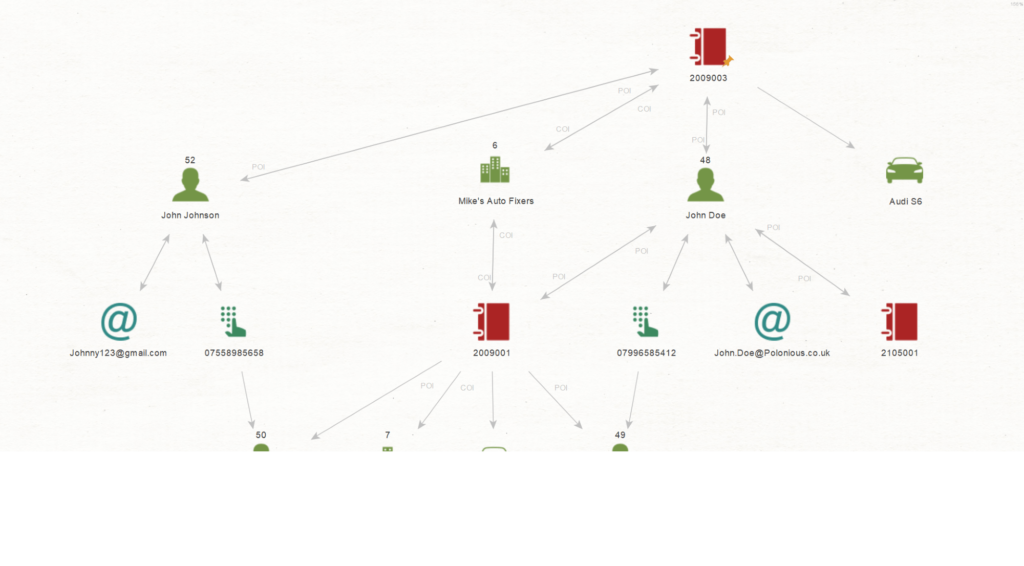

It can also help you identify networks of associates and possible leads toward the unexplained sources of income. In situations where the analysis isn’t admissible itself, this is still a useful tool for gathering, organising, and explaining evidence that is.

This is also where a case management solution like Polonious can help, for gathering and organising that evidence, particularly when combined with our integrations with OSINT sources, and Maltego graphical link analysis.

If you would like to speak to Polonious to see how we can make it easier to fight internal corruption, with our leading investigation management solution as the hub of your intelligence and investigation operations, please click here.

Let's Get Started

Interested in learning more about how Polonious can help?

Get a free consultation or demo with one of our experts

Nick Fisher

After being a client of Polonious while working in the Student Discipline team at Curtin University in Perth, Nicholas joined Polonious as a systems configurer in 2017. He since completed many successful rollouts as well as building Polonious' marketing team. Nicholas became CEO of Polonious when the founders retired in 2023.

Nicholas holds a Bachelor of Commerce, and a Bachelor of Arts with Honours in Philosophy from the University of Western Australia.